Reading your words. Seeing yourself.

On the particular strangeness of proofing your own book

I’m not sure which changed me more—the grief, or writing about the grief. Perhaps I’ll never know. But I am forever changed, for sure.

In a small town called Onomichi, overlooking the Seto Inland Sea in Japan, there is a spa hotel with an extraordinary wedding venue in its grounds. Designed by Hiroshi Nakamura, the Ribbon Chapel is formed of two giant interwoven spiral staircases rising up through the trees like a wooden homage to the double helix. But, unlike in DNA, in the case of the chapel the spirals join at the top. This building is what I think of when I think about the writing life.

We schedule our days as if life is linear, and we celebrate first books as the culmination of all our hard work, that culmination being an end point many debut authors cannot see beyond. But signing off my sixth book in six years I can tell you this: the writing life is more like a double helix than a straight line. One spiral represents our growth as a writer, and the other our growth as a human being. I imagine a thread running up through the centre of the double helix, representing the theme of our life. It’s the thing we keep being drawn back to whatever we write. For me this thread is about making the most of this precious life. I wonder what your theme is?

Every book we write takes us a little further up the writer spiral, and the living, healing and growing we have to do to get it written takes us a little further up the human spiral. There is a sculptural relationship between how we live and how we write. We see the central thread from all directions each time we travel around it. Getting that first book, poetry collection, screenplay or Substack essay out in the world is a fantastic achievement, but it is not the end, neither is it the only thing that matters. It is simply one loop of this beautiful, miraculous helix that intertwines writing and life in a constant dance.

In time we see how stories, ideas and inspiration live in everything around us, and how our lives are intimately intertwined with everything we ever write. Perhaps the longer we live the writing life, the closer the spirals get, merging like the staircases at the top of the Ribbon Chapel so that life is writing and writing is life.

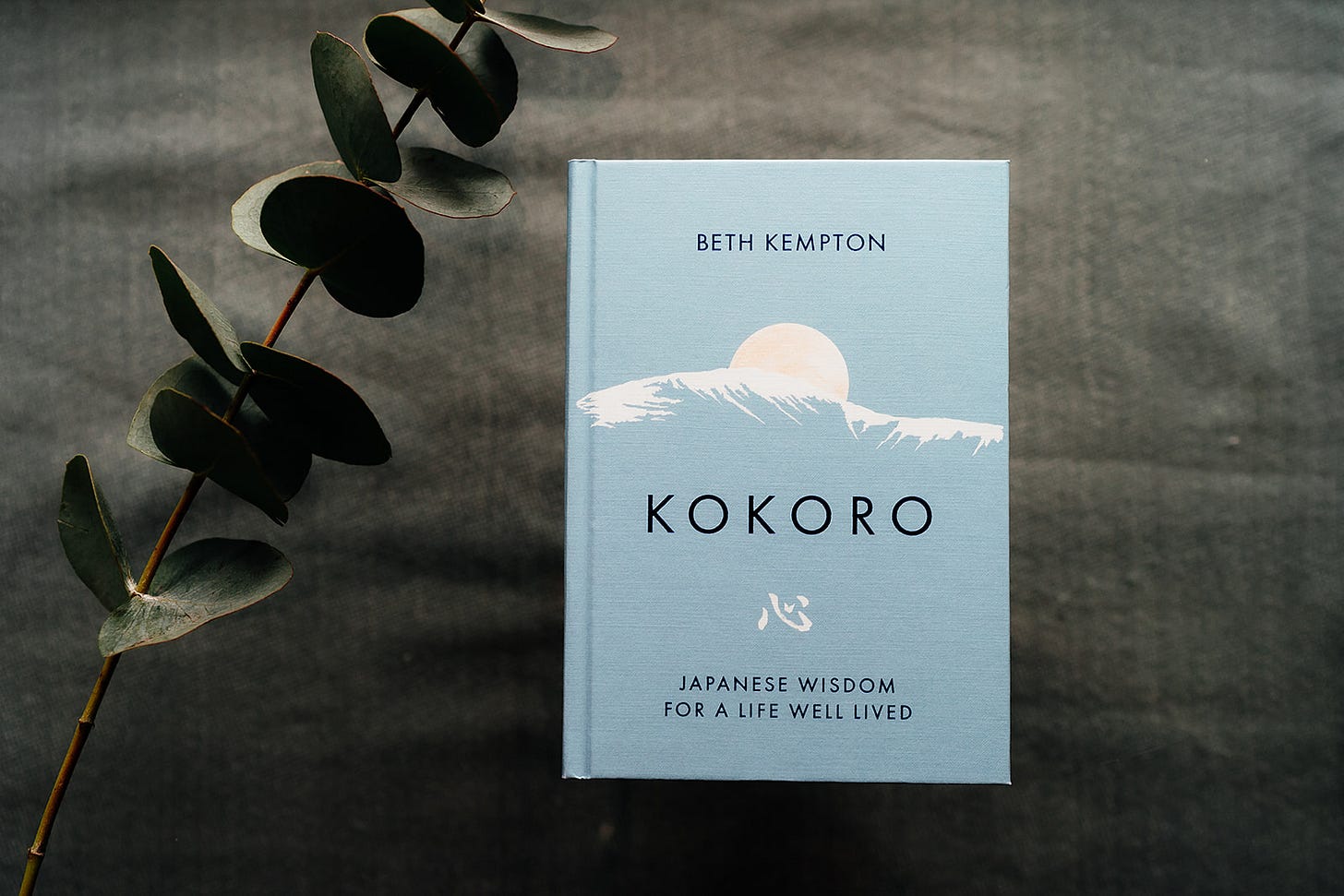

I have thought about this for a long time, but it has never been clearer to me than earlier this week, when I sat with the proof of my latest book Kokoro for one final time before it is signed off for publication. Today I thought I’d share about the particular strangeness of reading your own words at that unique threshold of the book proof – where it is very nearly done, but not yet out in the world.

I survived, am surviving, the story I had to live through to write this book and I survived the writing of the story which took me right back to all the hard places. That in itself, is something to be proud of, I think, although I take little credit for it, as I was just dosing myself with the medicine of words.

I handed in the manuscript at the end of September, and it came back to me last month for a single edit. Now it is back again, for one final check. A professional proofreader sees it too, but I always take a lot of care re-reading it myself that one last time. Normally I dive straight in, but this time it has been different.

The truth is my editor sent the proof through more than a week ago. I dutifully printed it off, punched holes in all the pages and neatly bound it in my finest A4 folder. Then I put it to one side on my desk and left it there.

Something stopped me opening the folder up to work on it. Perhaps it was the knowledge that once I read it once more it would mark the end of this particular time. Of course nothing is ever really finished, but there comes a point at which you can no longer drift through your days with a particular book as your companion, because you have to send it out with a defined shape in order for it to do its work in the world.

The thing no-one ever tells you about writing books is this: Each book you write diminishes you (it must, because you leave pieces of yourself within it) and expands you (it must because you had to live it to write it). You never really know the extent to which that will happen, or has happened, until you read the final version of the book and sense the gap between the person who wrote it (you, then) and the person who is reading it (you, now).

For days I tiptoed around the proof, leaning on the folder as I wrote Christmas cards, sensing it at the periphery of my vision as I worked on a new class, seeing it behind me in the background of a Zoom meeting, laying my hands on it, without opening it, before I switched off the fairy lights and shut the door of my writing room at the end of each day.

But on Monday, with the deadline looming, I put the folder in my bag, headed out of the door and promised not to return until it was done.

I wanted to choose somewhere special to read the proof for the final time. I thought I’d take it to a wine bar and toast my mum, whose loss back in the spring had scattered me like flakes from a salt shaker, but the bar was closed. I thought I’d go to a fancy hotel and imagine I was meeting my mum there for high tea. I went, but the offerings were expensive and I realised I wasn’t in the mood for eating cake alone, so I ordered coffee and sat on a velvet sofa for a while, until three hotel residents sat themselves next to me and started conversing so loudly I could not hear myself think. So I ended up back in a cosy cafe where I have spent many hours writing, which I had been to with my mum many times, and remembered how things don’t have to be fancy to be special.

And so it was with a view of the sea, the familiar rumble of low cafe chatter, and a steaming pot of tea, that I read through Kokoro twice – once to check for any rogue errors, and then once more, imagining a reader meeting her for the first time, going on a pilgrimage through rural Japan with me.

Checking a proof is time-consuming and stress-inducing – it’s your final chance to spot any typos. Inevitably some fall through the net, even with the most careful of editorial teams – I even have a page on my website where I gather all my book typos together, as an apology to readers and in recognition that there is no such thing as perfect. That said, I like to do my absolute best to check everything.

But then there comes a moment when you have to read it again differently – in my case I read it aloud quietly, because I will be recording the audiobook and I want to check, one last time, that every sentence flows. In this reading you experience your book in a different way. You meet yourself in all states of vulnerability, laid out on the page. It’s not an easy thing to do.

I read the first two chapters and remembered that’s all my mum got to read before I dropped everything to be with her in the three devastatingly short weeks between a terminal cancer diagnosis and her death, and how all the other chapters had to wait as everything unraveled. I remembered how she had said that she knew she wouldn’t get to read the rest, but she already knew what I would write, and she already loved it. I marvelled at how I somehow knew the structure of the book long before I knew the story that would fill it, and I wondered what kind of magic makes that possible.

The hours flew by as I travelled Japan’s remote back country once more, grappling with midlife malaise and grief, meeting sages in unexpected guises, climbing three mountains in as many days (still not quite sure how I managed that) and having the most powerful and important revelation of my life.

I remembered how, when I was working on Chapter 5 about losing my mum, I took my draft to the pub, ordered a glass of red wine - a large one in her honour, and put my AirPods in my ears. I picked a random jazz playlist from Apple and guess what came on? Gymnopedie No 1, a jazz version of her favourite piece of classical music, the piece that was playing when my brothers, Mr K and a childhood friend carried her coffin into her funeral gathering. This is what happens. All the time. When I was writing the Acknowledgements this week, the very last part of the book to be written, I ended it with a paragraph about my mum, then looked up from my desktop and through the window beyond and was greeted by the hugest, brightest rainbow I have ever seen.

Kokoro is a meditation on impermanence but it has a heat which is unusual for my work. As I read I sensed both companionship and loneliness, and I reached out towards the words wishing I could fix everything then remembering that I fixed what could be fixed and wrote about what could not, and reminding myself that not everything that breaks is meant to be fixed.

Kokoro has more of a memoir feel than my other books but it is still a self-help book of sorts. It explores the many questions we carry: How can we find calm in the chaos and beauty in the darkness? How do we let go of the past and stop worrying about the future? What can an awareness of impermanence teach us about living well? It is a book that dared me to explore the very nature of time, and of human existence, and investigate the way those two things are braided together.

This book carries the inky ashes of one of the toughest years of my life, a year of grief and loss and midlife everything. It also contains some of my most profound, hard-won life lessons. The sub-title is ‘Japanese wisdom for a life well lived’ and the book is about making the most of this wild and precious life. It is not a sad book. Of course there is desperate sadness in places, but also joy, lightness, laughter, deep conversations and trajectory-shifting revelations. It is a book about the complexity of life in all its shades of emotion. Ultimately it is uplifting – perhaps even life-changing as it has been for me in the writing of it, and in the living I had to do in order to write it. Only time will tell.

I remembered how, back in September, the manuscript deadline was looming ever closer, and I was starting to panic because I did not know how the book ended, and I kept reminding myself how the ending always reveals itself to me in time and hoping desperately that that would be true again. And then, just two days before the manuscript was due, the ending arrived under a bright autumn moon, and I knew the book was done.

I thought about the transitional stages of a book, always blurry and undefined as it shapeshifts from a vague idea to a proposal, from a proposal back to a vague wash of possibility and into the shape of a manuscript, and from that into a solid book you can hold which then vaporises into an idea or behaviour or other kind of imprint in the heart of a reader, and I realised that books are living, breathing things, which is probably why I am so reticent to part from this one, which has been a companion for half a decade.

I also wondered whether part of my reticence to let it go was because of the version of me it had encouraged to the surface – the version of myself willing to undertake one of the most challenging spiritual trainings in the world, the version who asked the questions no-one else was willing to ask and dared to be open to whatever answers might come, the version of myself that prioritised beauty and calm over striving. I like her. I don’t meet her often enough in my ordinary, domesticated life back at home, and I was afraid she would be trapped in the pages of the book if I let it go.

In reading the proof I can see how the extended trips I took to Japan for this book, twice for more than a month at a time in the past year alone, have been so exquisitely, outrageously different to my daily life that it’s no surprise someone said the blurb of the book sounds like a movie trailer.

I have two children. I have worked from home for twelve years. I live in the countryside and I don’t drive. The practical reality of my days is a lot of walking in fields and by the sea, sitting in cafes with my laptop, or in my home office, and doing family things. In the months after I lost my mum I didn’t want to talk to anyone really, so I rarely socialised. Then we went to Japan for the summer, and since we got back I have been so busy finishing this book and catching up on work that I have still barely socialised. I have spent much of the year traipsing through memory and turbulence in my inner world, using words to still the storm.

I guess my personal challenge for 2024 is to discover who I am now without this book by my side, under my skin, in my heart. I hope that one of your challenges for 2024 will be to see who you become in the reading of it, as it travels by your side, penetrates your skin, takes up residence in your heart.

As I finished reading the last line aloud, I remembered the moon, and the mountains, the shattering and the gratitude, and I closed the folder, and returned home.

Yesterday I typed up my notes, sent the email and made my way back into the kitchen of my life.

I put the kettle on, hugged my children, lit the advent candle and spent the rest of the day wrapping presents in an attempt to shake off the feeling I had just waved goodbye to an old friend at the station one last time.

Kokoro: Japanese wisdom for a life well lived is OUT NOW.

Photos: Holly Bobbins Photographer

Oh goodness. What a read. Yes, be so very proud. I was moved to tears that your mum knew what you'd write. I understand the fear of leaving yourself in the pages. I am very much looking forward to reading this special book. Wishing you and your family a very special happy Christmas, and as you said, special does not haven't be fancy. X

How beautiful, Beth. I cannot wait to read your new book ♥️