Unexpected lessons from a geisha house

On navigating midlife

The other day someone asked me how I plan travel itineraries that lead me to the kind of encounters I share in my new book Kokoro. It was hard to answer, because that isn’t really how it works. I tend to show up with a couple of things (but mostly spaciousness) in the diary and a ton of questions in my suitcase. I wander a lot, I take slow trains to small towns, I meet up with old friends and chat to strangers. Sometimes I share about my project, sometimes we talk about other things, until somehow the situation invites the project.

Doors open, often without any asking. There is a quick phone call, or a suggestion to meet again in three days’ time, or an offer to take me to meet someone if I have a spare hour. This is how I have met kimono designers, Noh masters, athletes, authors, monks and all kinds of contemporary pioneers.

And this is how I came to find myself pedalling as fast as I could down dark side streets in the oldest geisha district in Kyoto trying to find Umeno, a geisha house I was visiting by one such unexpected invitation.

There was a time that such establishments were simply off limits to people who did not have an ‘in’, and it was unheard of for foreigners to enter such establishments without a Japanese chaperone known to the okiya (the geisha house). Such rules have relaxed in recent years due to economic difficulties, but even so, in more than two decades of coming to Japan I had never been inside one. Until, that is, one random Saturday afternoon during a Kokoro research trip, when I met up with a friend in a café near Nanzenji temple in the east of the city. Noboru-san is a drone pilot who has a special licence from the Japanese government permitting him to fly his self-built drones inside the country’s most precious National Treasures, like Nanzenji. He loves nothing more than to showcase contemporary Japanese culture in a traditional context and his films are gorgeous (you can see them here) – he often pairs a famous dancer or sportsperson with a centuries-old important building to stunning effect.

We were just sitting there sipping our coffees and discussing his latest project, which involved filming a group of famous maiko* dancing, when he suddenly said, I think you’d really get on with Nakaji-san, the okāsan (‘Mother’) of the Umeno okiya. Would you like to meet her? Of course, I said, grateful for such a rare opportunity. (*In Kyoto, geisha are referred to as geiko, or maiko when they are young apprentices.)

Noboru-san took out his mobile, did a lot of bowing, and told me that if I could get there by 6pm, before everyone else arrived, I was welcome to stay all evening.

The Umeno okiya was established in 1977 - the year I was born – by Nakaji-san’s mother, Yoshie. Having trained in traditional dance since the age of five, she became a maiko at the age of 16. The entertainment district of Kamishichiken was established in the sixteenth century, apparently as a reward from samurai Hideyoshi Toyotomi to workers who had constructed the adjacent Tenmangu Shrine, (and used leftover materials to build). It is now the oldest and most traditional of Kyoto’s five geisha districts, which include Gion Kobu (the largest), Miyagawachō, Pontochō, and Gion Higashi.

I arrived on the dot of 6pm and was led to the empty bar in the heart of the okiya. Nakaji-san, and later her mother, would pop in and out to chat in between the arrival of guests. I stayed for hours, watching, listening, curious.

Three of the bar’s four walls were constructed from vertical slats of wood, spaced a breath apart, just wide enough to give a hint of the women moving gracefully along the wraparound corridor and then disappearing into rooms where clients were waiting. I felt like I was inside a spinning zoetrope catching rare glimpses of this world.

I might have presumed I would have little in common with the proprietor of a geisha house, who works at night in a world vastly different from my own, but the time spent together made me realise how wrong I was, and how similar we actually were. We were both women in midlife grappling with all kinds of questions, carrying inherited burdens, and trying to make good choices in the context of this uncertain, unpredictable life.

Nakaji-san told me how she grew up with her mother being a geiko and owner of the Umeno okiya, but had a ‘normal’ life outside of the geisha world, attending high school and working in an office. It was only through being on the outside that she could see the advantages of being on the inside, and given that in the geisha world okiya get passed down through the female bloodline, she made a decision to learn from her mother, after all. That was eighteen years ago.

Eventually Nakaji-san eventually took over the running of the business. It is a complex role, building and maintaining relationships, managing finances, and organizing events. Although business has long been tougher than in the heyday of Nakaji-san’s mother, it was doing fine until the pandemic hit.

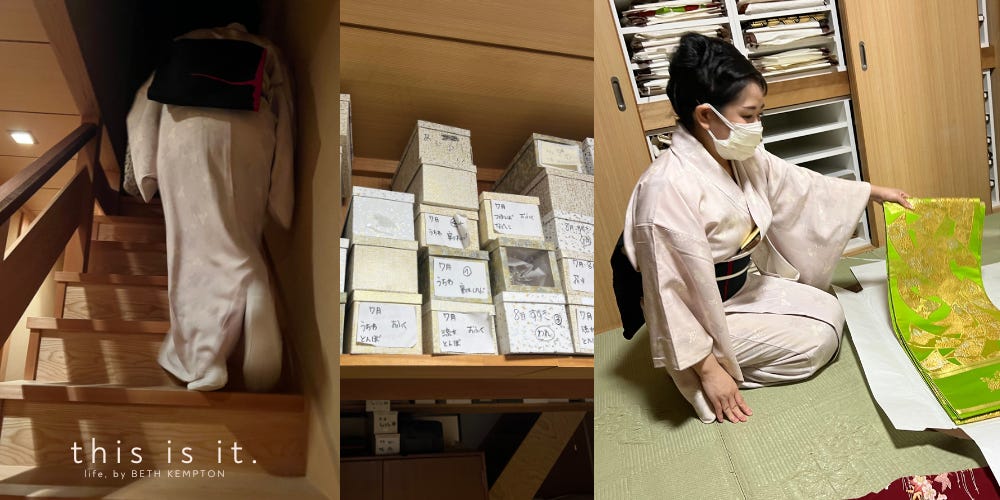

“Come and see this,” Nakaji-san said, leading me to the private quarters of the okiya, and showing me a treasure trove of kimono, silk flower hair accessories, labelled shoeboxes organised by month for seasonality, and all manner of other accoutrements needed to create such the iconic look.

Before the pandemic, there had been eight maiko and 20 geiko living and working within nine ochaya and five okiya in Kamishichiken, but COVID-19 decimated business, and the Umeno okiya can no longer afford to sponsor in-house geisha. Now they all work freelance, which came as a great shock to me, and Nakaji-san no longer has need for her vast stores of expensive clothing and accessories.

She pulled out drawer after drawer of folded kimono, some of them worth more than small cars, opening them carefully and casting reams of silk across the tatami floor.

At one point Nakaji-san wondered aloud how long she might keep doing this work, whether the okiya really is her path, or whether something else might be waiting for her. I sensed anticipatory grief in the way she carefully smoothed the kimono fabric, as she talked of how the geisha world is being forced to shapeshift into something new and unknown to avoid vanishing entirely. Kneeling on the floor against a backdrop of fabric which represents one of the most iconic parts of her culture, Nakaji-san acknowledged that the industry can only survive if it adapts to the shifting sands of the world.

Ever the entrepreneur, Nakaji-san told me of her plans to repurpose some of the beautiful garments into one-off dresses, handbags and other accessories, so people can carry a little heritage with them in a useable form. I could tell from her voice that she was smiling behind her COVID mask, but there was a deep sadness in her eyes – each of the garments has memories folded into its layers, and she knew that some of them would never again be worn by working geiko or maiko.

On reflection, that evening’s conversation was a very frank one given that we had only just met, and given that Nakaji-san swirls around in a secretive world. Many of the themes that came up when we chatted had also come up again and again over the past few years with local friends, in my online community, as well as with other contemporaries in Japan. The contexts might be different, but the challenges seemed virtually universal: To navigate any major life transition, including midlife, is to navigate grief. This is something I explore in depth in Kokoro.

There might be grief for the changes we are experiencing in our business (whether because things that used to work no longer work, the landscape has changed, or we are simply not as interested in it as we used to be). There may be grief for our changing relationships with ageing parents or growing children, or for children we couldn’t have, for people and pets we have lost and the days we cannot share with them, for relationships that have fallen apart, for the paths we did not choose and the decisions we regret, for people we have lost touch with, for the ways we did not celebrate, the things we missed in our desperate rush to be successful. And there is anticipatory grief as we stand at any major life threshold, for the things we now know we have to let die in order for us to fully live, for the people we know we will lose along the way and for the paths we cannot choose – because we cannot walk them all in this limited allocation of time and space that we call life.

Often, this grief is left unnamed and untended, so it wreaks havoc in our lives. We must acknowledge it all, get support where we need it, take good care of ourselves, and take the time to honour the person we have been at each stage, doing the best they could with the information they had and the situation they were in.

In the Japanese language, the most common word for regret is kōkai (後悔), which literally translates as ‘after-poison’. We suffer enough already. Let’s not poison ourselves too. We are vital and alive and each moment is a new opportunity to make the most of what we do still have available to us – an expansive, beautiful world full of many good people and much poetry, beauty and magic - and to make the best decisions we can with the information we have right now, and have the courage to listen to what the heart is telling us.

I was thrilled to get a DM from Nakaji-san recently, saying that she has embraced the inevitability of change within her industry and has finally launched a new arm of her business, selling exquisite one-off garments and handbags made from kimono once worn by geiko and maiko of Kyoto. You can see them here.

If you have enjoyed this brief encounter, and you too are navigating a life transition, then you might just love my new book KOKORO: Japanese wisdom for a life well lived, which is out now.

Beth Xx

Photos: Beth Kempton other than the image of Yoshie Nakaji (courtesy of Yuko Nakaji) and the giveaway image, by Holly Bobbins Photography

I have been looking at the transition in my own life from mother to crone. Upon turning 50 I hardly noticed death in the background because I was thoroughly immersed in menopause. Now, as I approach 60 this summer, I see death. Not with a morbid fascination, but a dawning realization that I am acquainting myself with a friend, who, when it is time, will take my hand. It unnerves my eldest daughter, so I have to be mindful of how I share. I’m not rushing towards my ending, but I wish to end well. Aware. Scattering the seeds of my life generously. Life. Death. Rebirth.

I just found your voice and I am so very grateful that I have.

Regret—> after-poison. Love that. But after what exactly? Regret has some value. It teaches us that when we did X we experienced consequence Y. Once we’ve learned everything we can from the feeling of regret, it’s no longer helpful. It’s after poison. But I wonder whether there’s another word that describes the healthy negative feeling that precedes after-poison.